(read the article in English at the end of the story in portuguese)

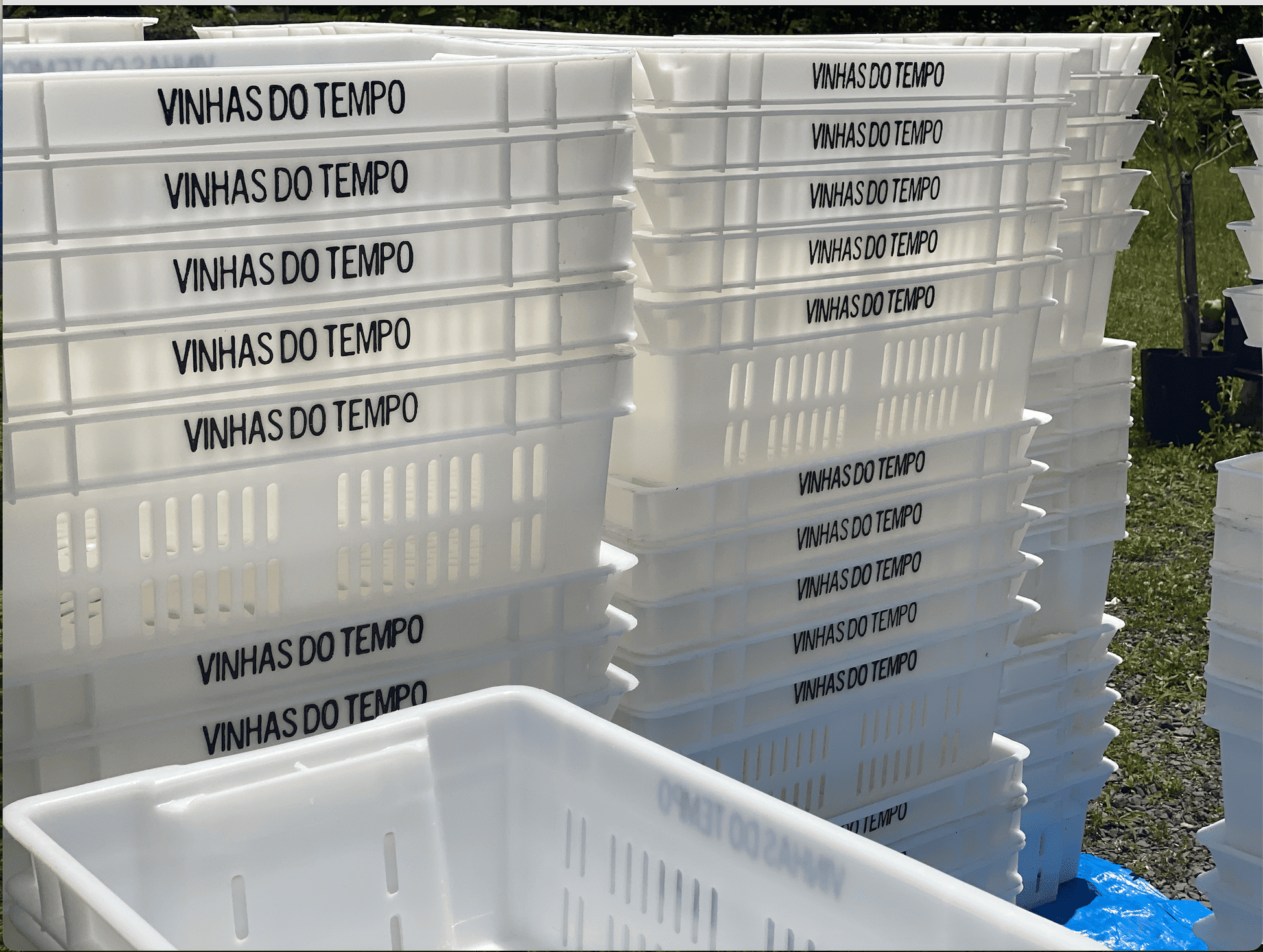

Os ruídos dos caminhões e das pequenas carretas são trilha sonora no verão em boa parte do Brasil, principalmente na Serra Gaúcha. Os veículos passam carregando caixas vazias no escuro da madrugada e voltam cheios de uvas ainda pela manhã, antes do sol subir e começar a esquentar os frutos que idealmente devem chegar ainda frescos às cantinas para passarem por uma importante etapa do maravilhoso processo de transformar uva em vinho: a vinificação.

Estar em cidades como Monte Belo do Sul, Bento Gonçalves, Garibaldi, Farroupilha e Pinto Bandeira nesta época é respirar a cultura do vinho e da uva. Em rápidos três dias, podemos ver muito. E sim, testemunhar como é árduo o trabalho do viticultor e do produtor de vinho, principalmente quando pequeno e quando faz da filosofia da baixa intervenção uma das marcas de sua vinícola.

Abaixo algumas impressões de um final de semana comprido – e cumprido também, porque trabalhamos na colheita e na vinificação – no coração da região vitivinícola do Brasil.

Começamos por Monte Belo do Sul

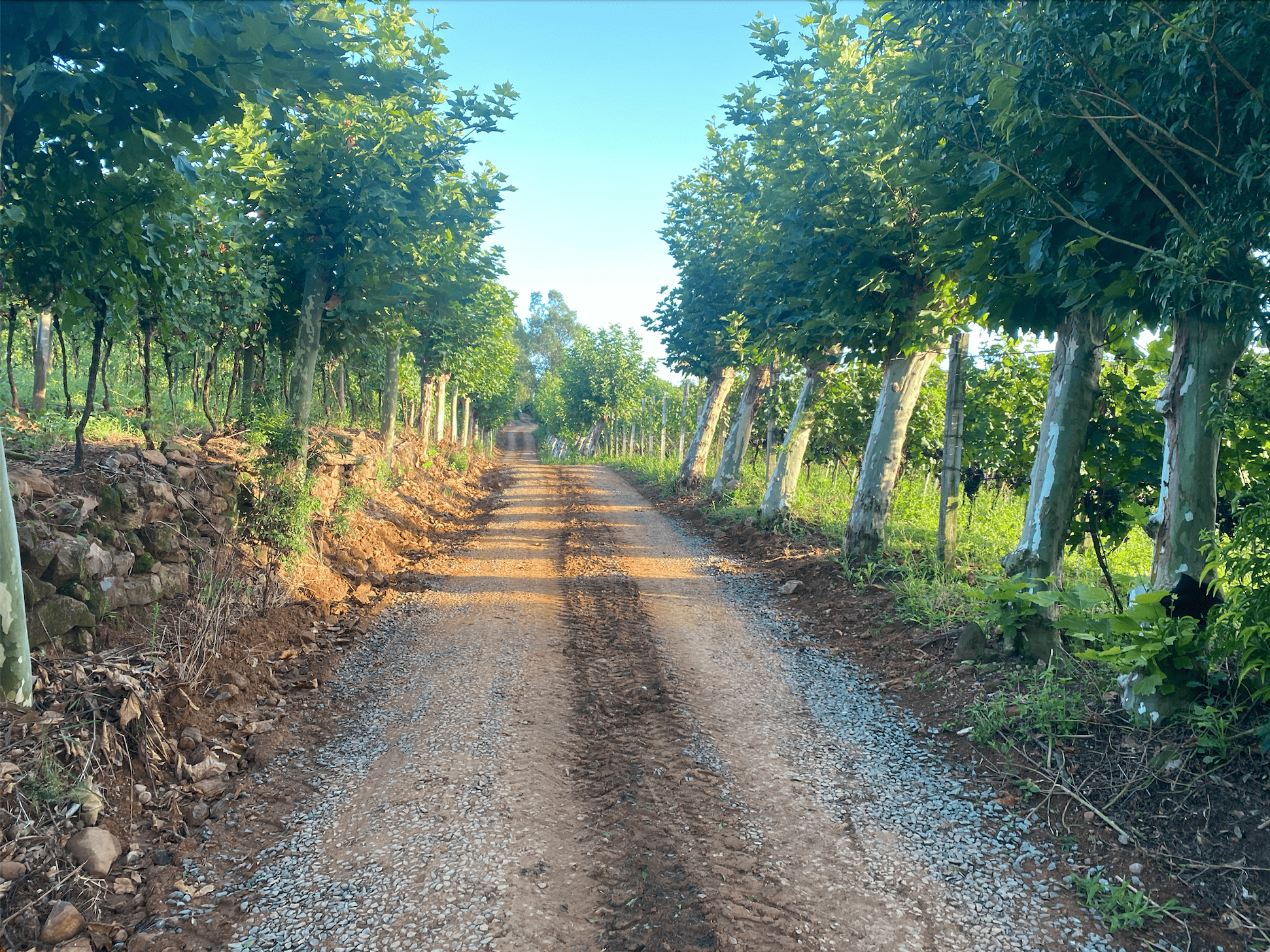

Uma linda cidade encravada no topo dos Vale dos Vinhedos, cerca de 130 quilômetros distante de Porto Alegre. Pequena, com uma população de acordo com o IBGE, de menos de 3 mil pessoas. Daquelas cidades que têm a Praça e a Igreja como pontos principais, onde se ouve os pássaros o dia todo e os moradores se cumprimentam em todas as esquinas.

Monte Belo também é a cidade do Brasil onde há a maior produção de uva fina per capita do país – cerca de 16 toneladas/ano, cultivadas em mais de 600 propriedades em uma área de mais ou menos 20 quilômetros (pegando um trecho de Bento Gonçalves e da cidade vizinha de Santa Tereza para fins de Indicação de Procedência). Reconhecido como IP desde 2013, Monte Belo do Sul também é um município muito lembrado pela concentração de produtores orgânicos, biodinâmicos, naturais, autorais ou de pouca intervenção – são coisas diferentes, mas sim, isso é outra matéria.

Então, às vinícolas.

Vinhas do Tempo

A casa do vinhateiro poderia ser a ilustração da marca da sua vinícola, a Vinhas do Tempo. Talvez o sorriso dele em frente à porta de entrada da cantina também seja um pouco parte disso: lá em cima, no alto de Monte Belo, o tempo parece parar. Mas paradoxalmente – como o tempo, que à medida que envelhecemos anda mais rápido – ao entramos na cantina e fecharmos a porta atrás de nós, somos transportados para outra dimensão, mas ali o tempo voa e escoa pelas nossas mãos.

Uma manhã é curta para ouvir o Daniel Lopes contar a sua história com o vinho e com a Vinhas. O guri que estudou nos Estados Unidos na adolescência e anos depois se formou em Comércio Exterior, adora tabelas, simetria, organização e é o rei das exatas, trabalhava de fatiota, como ele diz, até que um dia resolveu mudar. Também pudera – o pai, amigo do estrelado Wilmar Bettú levava o piá pra cantina do vinhateiro, em Bento Gonçalves. Com o perdão do trocadilho, Dani foi tomando gosto e passou a ajudar o amigo do pai informalmente. E quem se envolve com vinho sabe, na hora que a bebida entra no sangue, já era.

Com vontade de trabalhar e aprender, voltou ao Bettú, dessa vez pra prestar mais atenção e conhecer mais a fundo. Mas Dani queria experimentar e resolveu estudar fora do Brasil: em 2014 fez a mala e foi estudar na França. O curso que achou, Wine Business, era na Borgonha – pensa que destino para um cara que ama vinhos mais delicados, neutros e minerais. “Foi o acaso”, diz Dani, “era o curso mais barato, todo em inglês e aproveitava muito do que eu já tinha estudado. Então eu fui”.

E lá era o único brasileiro da turma, ficou por quase dois anos morando em Dijon, aprendendo com professores do mundo todo. Estudou por lá – além do curso onde estava matriculado fez também as etapas 2 e 3 do WSET, trabalhou, bebeu bastante, conheceu diferentes vinhos – entre eles, os naturais.

“Foi ali que deu um clique na minha cabeça”, lembra o vinhateiro.

O clique se deu com um vinho da uva Grolleau, de um produtor do Vale do Loire bem pequeno na época, François Saint-Lô. “Era um vinho diferente, uma coloração rosa meio chiclete, levemente turvo, álcool e tanino super baixos…lembro que perguntei: mas e isso é vinho?”E então explicaram para o futuro vinhateiro os métodos de vinificação – era um um vin de soif como se fala na França, ou um vinho feito pra ‘matar a sede’. “Aquilo ficou na minha cabeça, comecei a ir atrás de vinhos assim, conheci muito produtor desse estilo, visitei o Saint-Lô, me apresentei pra ele, que me abriu as portas e apresentou todos os vinhos. Fui super bem recebido”.

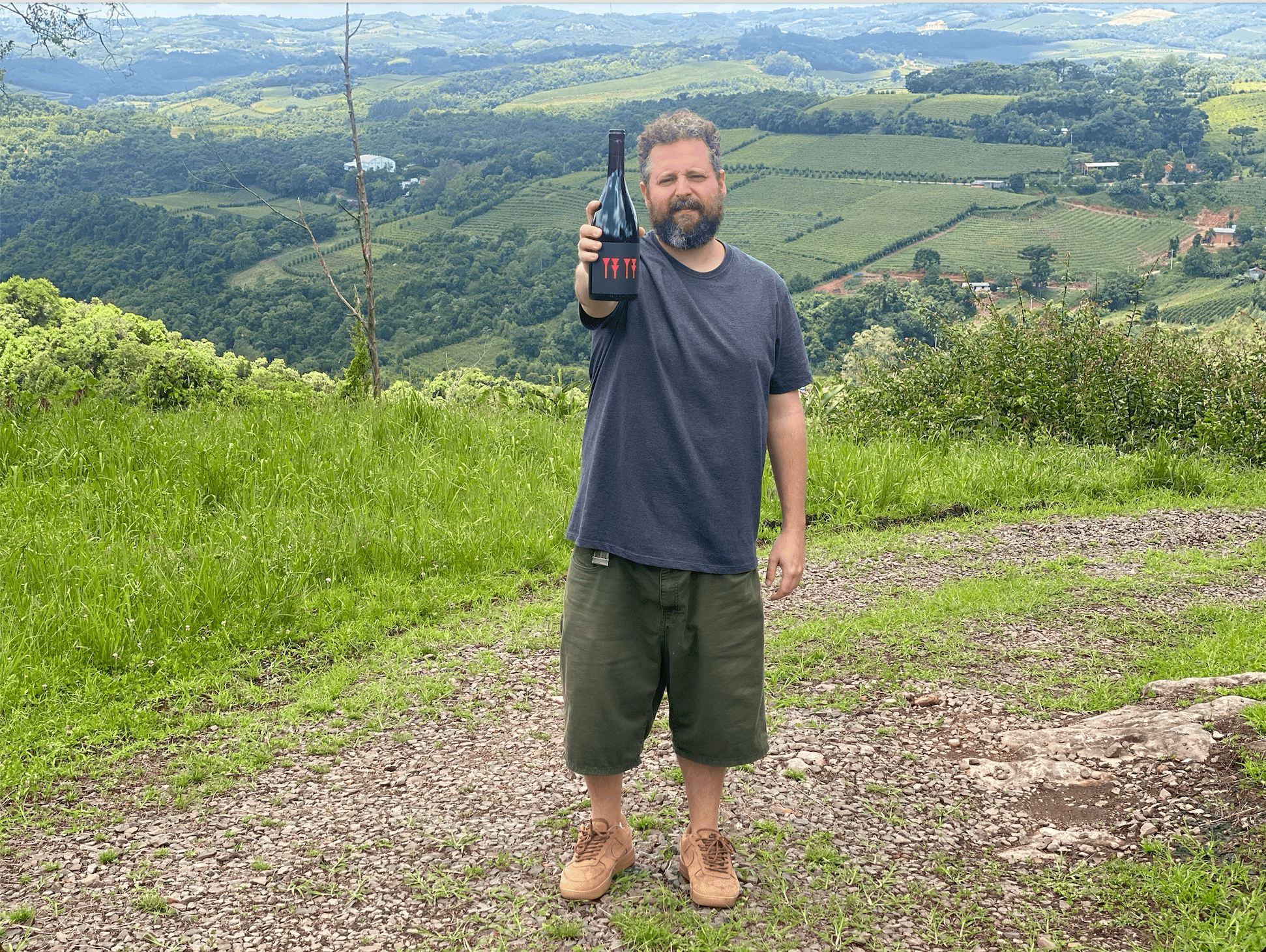

Hoje Daniel Lopes tem em seu portfolio um cuvée cofermentado com esse perfil de beber fácil, mas a Vinhas do Tempo é reconhecida como uma vinícola especializada em tranquilos, rótulos de Pinot Noir e Chardonnay – algmuas vezes também Gamay – que estagiam em madeira, além do pét-nat.

Aliás, foi com um pét-nat – pétillant naturel, termo francês que significa ‘efervescente natural’ ou ‘espumante natural’, expressão que nasceu no Vale do Loire no final dos anos 90 – que a Vinhas do Tempo começou a aparecer no mercado, em 2017. As redes sociais foram o veículo perfeito para apresentar aos brasileiros aquele vinho diferente, que vinha numa garrafa transparente, tinha um rótulo colorido e uma tampinha tipo as de cerveja. O pét-nat IN VITRO, de Pinot Noir – cultivada por um parceiro em Encruzilhada do Sul, no mesmo vinhedo, mesma parcela e mesmas fileiras desde sempre – foi metade da primeira safra de 800 garrafas da vinícola. Hoje a Vinhas do Tempo faz cerca de 5 mil garrafas de vinho por ano. Mas quem acha que isso é fácil se engana: dá pra trabalho chegar até aqui.

“Vinho: metade do tempo limpando sujeira e metade do tempo carregando peso. Não tem esse glamour que se tenta dizer por aí.” Essa frase, claro, é do Dani.

Mas a ideia não é estacionar: Dani tem planos de ampliar a vinícola, implantar um pequeno vinhedo – para estudar, experimentar e aprender – e o sonho de vinificar no exterior – na Borgonha, o começo e o fim de tudo, para quem sabe fechar um ciclo?

Mas enquanto esse momento não acontece, o vinhateiro comemora a primeira exportação, que em 2023 levou seus rótulos ao Perú, onde estão nas cartas de restaurantes estrelados como o Central – eleito melhor do mundo pelo 50th Best em 2023. Em 2024 a Vinhas do Tempo deve ter garrafas exportadas para os Estados Unidos, mas Singapura e França também estão nos planos.

“Quem tem pressa não faz vinho”, diz o Dani.

E devagar se vai ao longe, podemos complementar.

Seis Mãos

No dia anterior a Carol confirmou umas duas ou três vezes o horário que nos encontraríamos para pegar o transporte e ir até o local da colheita. Ainda de madrugada, a pergunta era necessária: é seguro deixar o carro na praça enquanto estivermos lá? A resposta da Carol foi sucinta: “tu corres o risco de quando voltar ele estar no mesmo lugar”.

(quando voltamos, estava lá, claro)

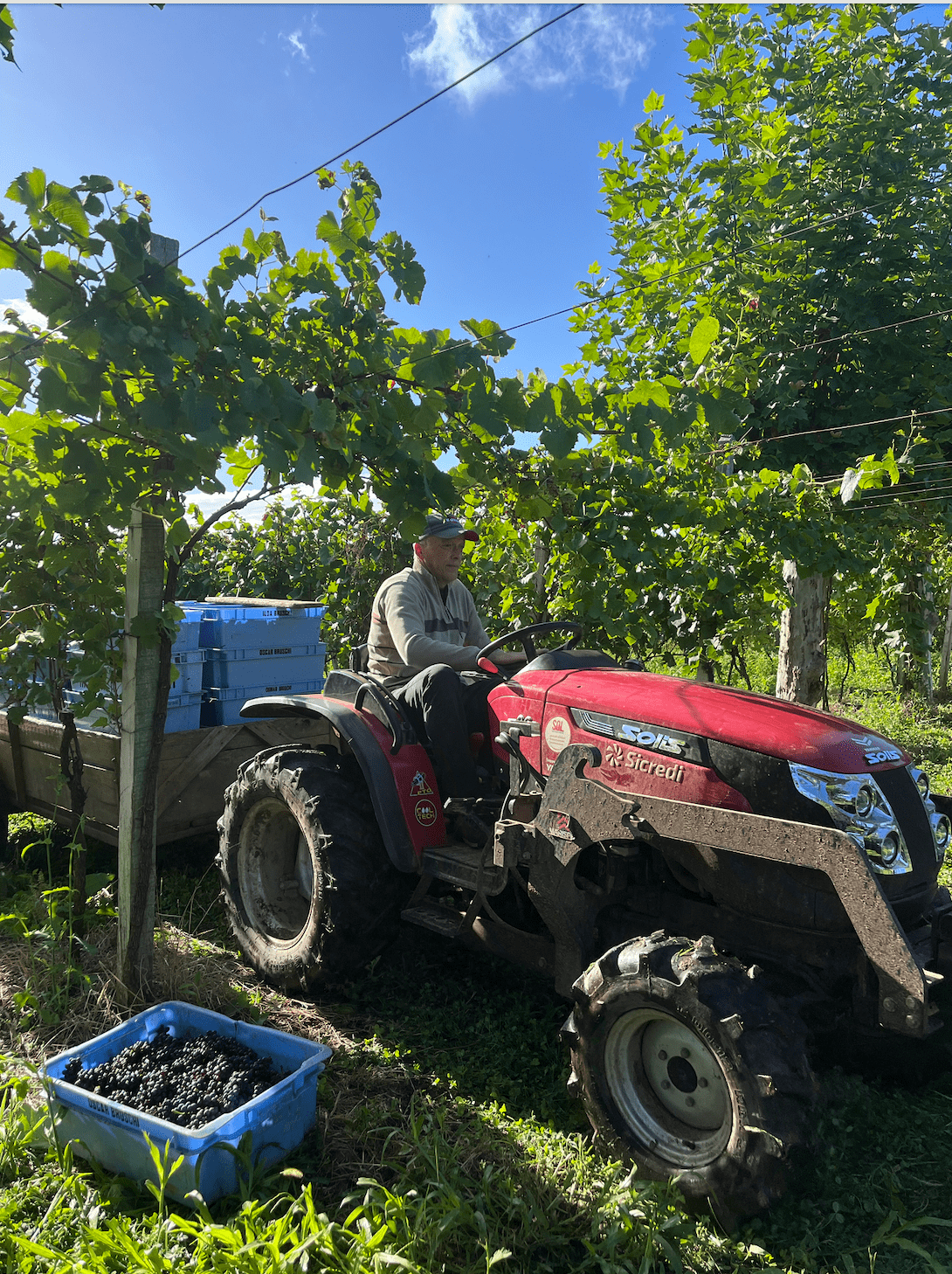

E lá fomos para o vinhedo no 100 da Leopoldina, no interior de Monte Belo do Sul, propriedade de Oscar Bruschi, produtor de uvas que Carol conheceu batendo um papo na Tanoaria Mezacasa, empresa que produz as barricas de madeira brasileira que utiliza em seus vinhos. Conversa vai, conversa vem, Carol pergunta: Oscar, que uvas tu plantas? Entre tantas variedades, a Pinot Noir. E era essa que ela queria. Negócio fechado, e há três anos essa situação se repete a cada safra.

Repelente, boné e boa vontade, fomos colher, mas fomos ter aula também. Além de ensinar a retirar os cachos sem machucar, a enóloga Caroline Gonzatti, proprietária da vinícola Seis Mãos – agora devidamente apresentada – discorre sobre as características da variedade, aponta eventuais problemas nas uvas – bem poucos, por sinal – e transmite uma alegria genuína de quem é apaixonada pelo que faz, o que deixa um trabalho cansativo mais leve e fácil de desempenhar.

Algumas horas depois, tarefas finalizadas (logicamente com o auxílio de uma equipe profissional que estava ali fazendo um trabalho sério), foram recolhidas 57 caixas de Pinot Noir – que depois descobrimos resultaram em 850 quilos de fruta – que seriam transportadas para cantina, onde vem mais uma etapa de trabalho – cansativo e que exige muita atenção, mas é hipnotizante.

A vinificação

Um processo que começa bem antes da uva chegar à cantina. Na verdade, é um ciclo que nunca termina, pois a limpeza, a higiene e a organização são fundamentais. Cada tanque, cada recipiente, cada máquina, cada medidor, cada termômetro, cada pipeta, taça, o chão: tudo precisa ser limpo, limpo mais uma vez e então limpo novamente. No caso da Seis Mãos, o tempo que separa o final da colheita da entrega das uvas pelo produtor parceiro, é preenchido com conferências, organização e mais limpeza. Mastelas higienizadas, desengaçadeira brilhando, leveduras organizadas, instrumentos em seus locais.

Recebidas as uvas, são pesadas imediatamente e passam pelo processo de desengace – as bagas são separadas do engaço, o cabinho – em um processo apelidado carinhosamente de ‘bate caixa’. Pensem no som das caixas cheias de uvas batendo no equipamento de metal. No caso da Pinot, multipliquem este barulho por 57 vezes: bate caixa. Simultaneamente o mosto começa a preencher a mastela de madeira, onde ficará pelo tempo que a enóloga achar mais adequado.

O processo descrito acima parece simples, mas lembre: no caso da Pinot, foram 57 caixas ou 850 quilos de fruta. Neste dia começamos pela Chardonnay, colhida em outro vinhedo na mesma região: 500 quilos de fruta, nem deu tempo de contar a quantidade de caixas, mas faça um exercício mental.

Horas depois, mastelas preenchidas, momento de fazer o Pé de Cuba – em outras palavras, diluir um preparado para adicionar leveduras ao mosto e aguardar a fermentação. É algo muito interessante e sério: fazendo as coisas na prática percebemos mais claramente a importância do conhecimento e da técnica na elaboração dos vinhos. E valorizamos ainda mais quem tem segurança e confiança para realizar estes processos fundamentais e tão delicados.

Sobre a vinícola

Pra quem não conhece a Seis Mãos, fica a dica. Um projeto que começou informalmente lá em 2014, quando a Carol Gonzatti fez em casa seu primeiro espumante de Chardonnay. Em 2022 a vinícola foi legalizada e passou a ter o registro no MAPA. O porquê da marca? Seis Mãos, para Carol representam o ciclo do vinho: o agricultor, o enólogo e o tanoeiro, para ela figuras fundamentais no desenvolvimento do produto.

E sobre o vinho que começamos a vinificar no final de janeiro de 2024? Agora é esperar o tempo do vinho e da enóloga.

Pinto Bandeira

Saímos de Monte Belo do Sul e dirigimos cinquenta e poucos quilômetros até a última parada, em Pinto Bandeira, município conhecido pela alta qualidade de seus espumantes. Qualidade aliás tão reconhecida que desde novembro de 2022 os rótulos produzidos por quatro vinícolas da região – Valmarino, Aurora, Geisse e Don Giovanni – podem ostentar o selo da Denominação de Origem Altos de Pinto Bandeira em seus rótulos, a única D.O. de Espumantes do Novo Mundo.

Vinhedos Altos da Pinta

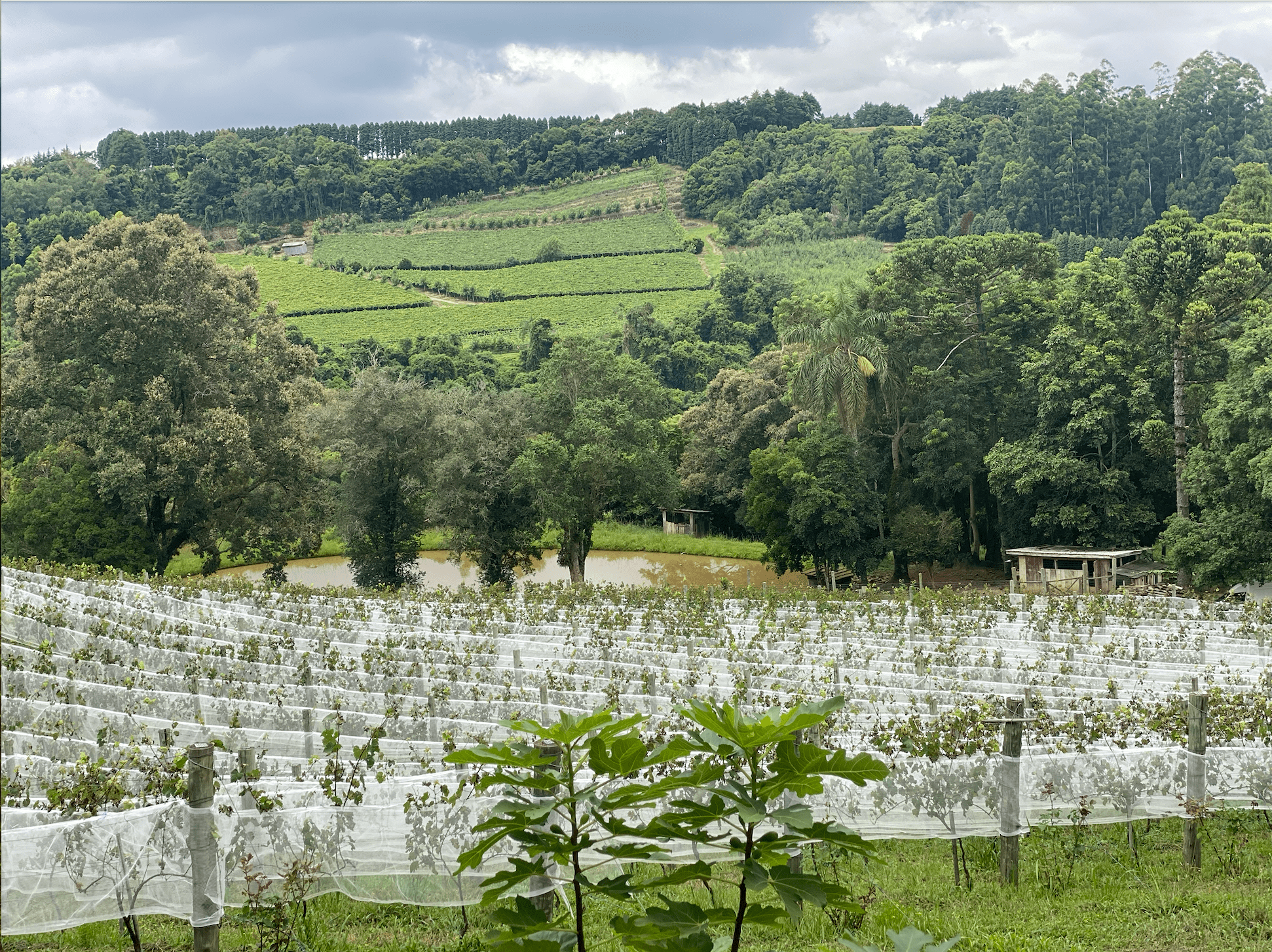

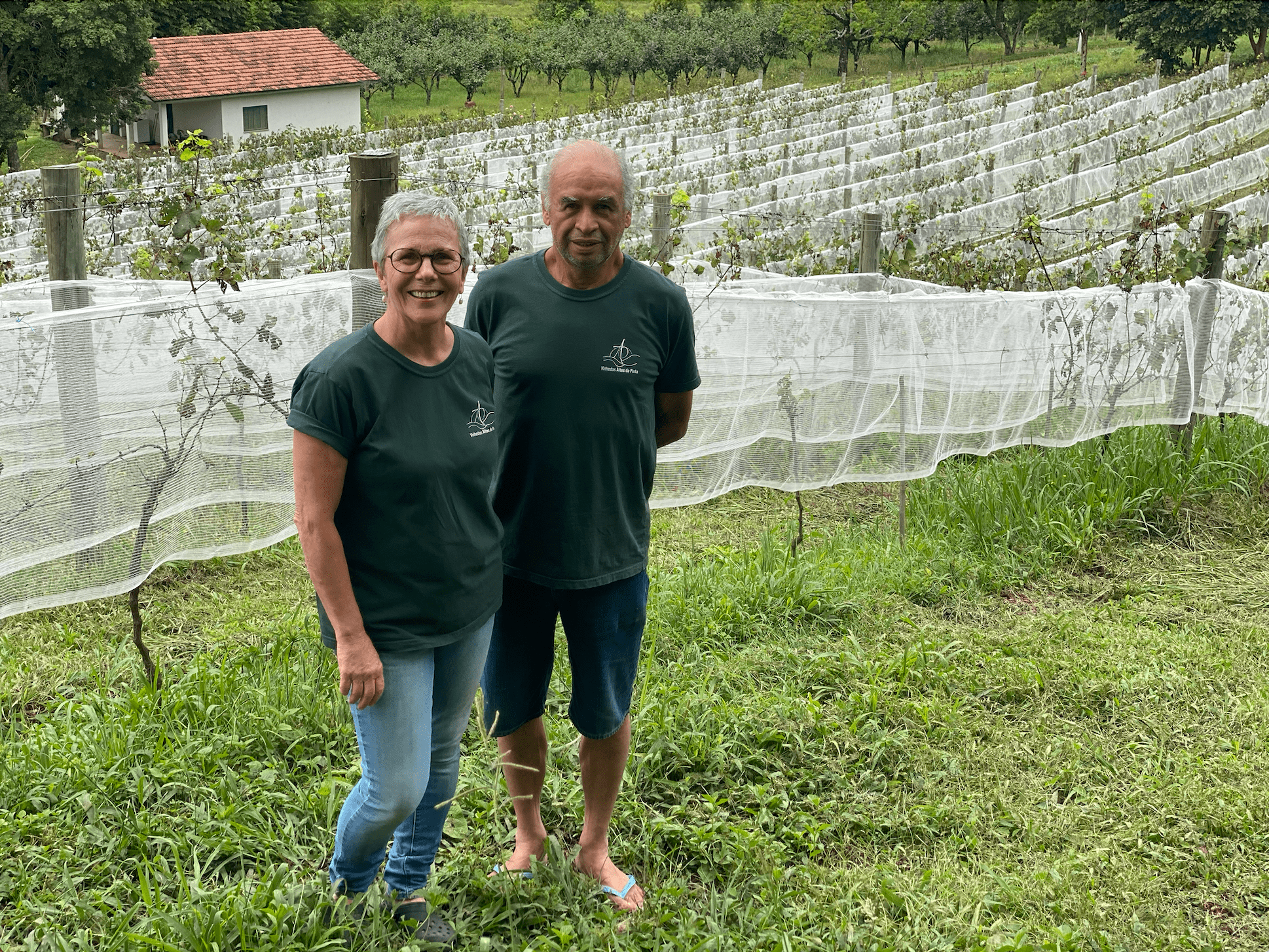

Nosso destino foi o Vinhedos Altos da Pinta, propriedade não muito fácil de achar – mas que bom desta forma, diríamos, um lindo e sossegado refúgio, onde vive o casal Pedro Maciel e Renata Salvadori Rizzotto, ele jornalista e ela arquiteta, em meio à natureza e às fileiras de Chardonnay.

Na frente, na área que já produz, são 1,7 mil mudas, plantadas em 2017. No fundo do terreno, um espaço maior tem outras 3,7 mil mudas da mesma variedade, plantadas em 2020, todas vindas de Friuli, na Itália. Nos próximos anos a ideia é também plantar Pinot Noir, uva clássica do corte dos elegantes e premiados espumantes da região.

Projeto de vida

Mas por que fazer vinho? “O vinho virou um projeto de vida”, diz Pedro. Ao se aposentar o casal pensou em duas hipóteses: morar na praia e não fazer nada ou mudar pra Serra e fazer vinho. A dupla, que desde sempre compartilhou hábitos de alimentação saudável, optou pelo vinho. “Acho que somos loucos”, brinca Renata. “Ainda mais com essa opção de biodinâmicos”, completa.

O vinhedo, certificado pela Demeter, segue a filosofia de Rudolf Steiner, utiliza dos preparados, acompanha as fases da lua e tem intervenção praticamente zero. A colheita é feita na lua ascendente, lua cheia, o que significa, conta Renata, que tem muita seiva na planta, nas folhas e nas frutas. “Nossa próxima colheita será em dia de fruta, ascendente, lua cheia e Leão, tudo favorece”, explica Renata. “Fazemos o vinho que achamos que é correto. E cada vinho é correto para cada pessoa: tem espaço pra todos”, explica Pedro.

“Se o biodinâmico tem ainda uma desvantagem é por ser pouco conhecido, isso faz com que ele seja mais caro, o que complica a venda do produto”, sentencia. De acordo com Pedro, o bebedor de vinho biodinâmico ou conhece o produto ou é um curioso por experimentar coisas novas – “e quando degusta, costuma gostar”, complementa.

Os dois rótulos de Chardonnay dos Altos da Pinta – um espumante e um tranquilo – são produzidos a partir de leveduras autóctones ou indígenas – aquelas que ocorrem naturalmente em cada região e desta forma garantem tipicidade à bebida – não passam por filtragem, chaptalização, não têm aditivos nem clarificantes e recebem menos que o mínimo autorizado de sulfito. “Fazemos o vinho da uva”, sentencia Pedro.

Todo esse cuidado – e porque não dizer restrições – cobra sua conta: em 2023, por exemplo, a Altos da Pinta produziu apenas 139 garrafas, pense em produção artesanal. A expectativa, segundo Renata, era cerca de 2 mil unidades: “mas aí teve geada, chuva e passarinhos”.

Com relação às intempéries não se pode ir contra, mas os pássaros tem mais um obstáculo, o vinhedo está todo protegido contra eles.

Para sugestões de matérias escreva para [email protected]

Texto e fotos: Lucia Porto, na foto preparando o Pé de Cuba. Sob supervisão, claro.

Three days harvesting in Serra Gaúcha

The noise of trucks and small trailers is the soundtrack in summer in much of Brazil, especially in Serra Gaúcha. Vehicles pass by carrying empty boxes in the dark of dawn and return full of grapes in the morning, before the sun rises and begins to heat the fruits, which ideally should arrive still fresh at the canteens to go through an important stage in the wonderful process of transforming grapes into wine: winemaking.

Being in cities like Monte Belo do Sul, Bento Gonçalves, Garibaldi, Farroupilha and Pinto Bandeira at this time is like breathing in the culture of wine and grapes. In a quick three days, we can see a lot. And yes, witness how hard the work of wine growers and wine producers is, especially when they are small and when they make the philosophy of low intervention one of the hallmarks of their winery.

Below are some impressions of a long weekend – and also fulfilled, because we worked on harvesting and winemaking – in the heart of Brazil’s wine region.

We start with Monte Belo do Sul

A beautiful city nestled at the top of the Vale dos Vinhedos, about 130 kilometers away from Porto Alegre. Small, with a population, according to IBGE, of less than 3 thousand people. Those cities that have the Square and the Church as their main points, where you can hear the birds all day long and residents greet each other on every corner.

Monte Belo is also the city in Brazil where there is the largest production of fine grapes per capita in the country – around 16 tons/year, cultivated in more than 600 properties in an area of more or less 20 kilometers (taking a section of Bento Gonçalves and the neighboring city of Santa Tereza for Indication of Origin purposes). Recognized as an IP since 2013, Monte Belo do Sul is also a municipality well known for its concentration of organic, biodynamic, natural, copyright or low-intervention producers – they are different things, but yes, that is another matter.

So, to the wineries.

Vinhas do Tempo winery

The winemaker’s house could be an illustration of the brand of his winery, Vinhas do Tempo. Maybe his smile in front of the cantina’s entrance door is also a little part of this: up there, at the top of Monte Belo, time seems to stop. But paradoxically – like time, which moves faster as we get older – when we enter the canteen and close the door behind us, we are transported to another dimension, but there time flies and flows through our hands.

A morning is too short to listen to Daniel Lopes tell his story with wine and vineyards. The boy who studied in the United States as a teenager and years later graduated in Foreign Trade, loves tables, symmetry, organization and is the king of exacto, he worked in a suit, as he says, until one day he decided to change. He could have done it too – his father, a friend of the star Wilmar Bettú, took Piá to the winemaker’s cantina, in Bento Gonçalves. Pardon the pun, Dani began to enjoy it and began to help her father’s friend informally. And anyone involved with wine knows, the moment the drink enters the blood, it’s gone.

Wanting to work and learn, he returned to Bettú, this time to pay more attention and learn more in depth. But Dani wanted to try it and decided to study outside Brazil: in 2014 she packed her suitcase and went to study in France. The course he found, Wine Business, was in Burgundy – think what a destination for a guy who loves more delicate, neutral and mineral wines. “It was chance”, says Dani, “it was the cheapest course, all in English and it took advantage of a lot of what I had already studied. So I went”.

And there he was the only Brazilian in the class, he spent almost two years living in Dijon, learning from teachers from all over the world. He studied there – in addition to the course he was enrolled in, he also took stages 2 and 3 of the WSET, worked, drank a lot, got to know different wines – including natural ones.

“That’s when it clicked in my head”, recalls the winemaker.

The click happened with a wine from the Grolleau grape, from a producer in the Loire Valley that was very small at the time, François Saint-Lô. “It was a different wine, a bubblegum pink color, slightly cloudy, super low alcohol and tannin… I remember asking: but is this wine?” And then they explained the winemaking methods to the future winemaker – it was a vin de soif as they say in France, or a wine made to ‘quench your thirst’.

The click happened with a wine from the Grolleau grape, from a producer in the Loire Valley that was very small at the time, François Saint-Lô. “It was a different wine, a bubblegum pink color, slightly cloudy, super low alcohol and tannin… I remember asking: but is this wine?” And then they explained the winemaking methods to the future winemaker – it was a vin de soif as they say in France, or a wine made to ‘quench your thirst’. “That stuck in my head, I started looking for wines like that, I met a lot of producers of that style, I visited Saint-Lô, I introduced myself to him, who opened the doors to me and presented all the wines. I was very well received.”

Today Daniel Lopes has in his portfolio a co-fermented cuvée with this easy-drinking profile, but Vinhas do Tempo is recognized as a winery specializing in still wines, Pinot Noir and Chardonnay labels – sometimes also Gamay – which age in wood, in addition to pét-nat.

In fact, it was with a pét-nat – pétillant naturel, a French term that means ‘natural effervescent’ or ‘natural sparkling wine’, an expression that was born in the Loire Valley in the late 90s – that Vinhas do Tempo began to appear on the market, in 2017. Social media was the perfect vehicle to introduce Brazilians to that different wine, which came in a transparent bottle, had a colorful label and a beer-like cap. Pét-nat IN VITRO, from Pinot Noir – grown by a partner in Encruzilhada do Sul, in the same vineyard, same plot and same rows since always – was half of the winery’s first harvest of 800 bottles. Today Vinhas do Tempo makes around 5 thousand bottles of wine per year. But anyone who thinks this is easy is wrong: it takes work to get here.

“Wine: half the time cleaning up dirt and half the time carrying weight. It doesn’t have that glamor that people try to say.” This phrase, of course, is from Dani.

But the idea is not to park: Dani has plans to expand the winery, establish a small vineyard – to study, experiment and learn – and the dream of making wine abroad – in Burgundy, the beginning and end of everything, for those who know how to close a cycle?

But while this moment does not happen, the winemaker celebrates his first export, which in 2023 took his labels to Peru, where they are on the menus of starred restaurants such as Central – voted best in the world by 50th Best in 2023. In 2024, Vinhas do Tempo bottles should be exported to the United States, but Singapore and France are also in the plans.

“Those who are in a hurry don’t make wine”, says Dani.

And slowly it goes a long way, we can complement it.

Seis Mãos winery

The day before, Carol confirmed two or three times the time we would meet to take transport and go to the harvest location. Even in the early hours of the morning, the question was necessary: is it safe to leave the car in the square while we are there? Carol’s response was succinct: “you run the risk that when you return he will be in the same place”.

(when we came back, it was there, of course)

And there we went to the vineyard at 100 da Leopoldina, in the interior of Monte Belo do Sul, owned by Oscar Bruschi, a grape producer that Carol met while chatting at Tanoaria Mezacasa, a company that produces the Brazilian wood barrels that it uses in its wines. Conversation goes on and on, Carol asks: Oscar, what grapes do you grow? Among so many varieties, Pinot Noir. And that was what she wanted. Deal closed, and for three years this situation has been repeated with each harvest.

Repellent, cap and good will, we went to collect, but we also went to class. In addition to teaching how to remove the bunches without hurting them, winemaker Caroline Gonzatti, owner of the Seis Mãos winery – now properly presented – talks about the characteristics of the variety, points out any problems with the grapes – very few, by the way – and conveys a genuine joy of who is passionate about what they do, which makes tiring work lighter and easier to perform.

A few hours later, tasks completed (of course with the help of a professional team that was there doing serious work), 57 boxes of Pinot Noir were collected – which we later discovered resulted in 850 kilos of fruit – which would be transported to the canteen, where it comes from. another stage of work – tiring and requiring a lot of attention, but it is mesmerizing.

The winemaking

A process that begins well before the grapes arrive at the canteen. In fact, it is a cycle that never ends, as cleaning, hygiene and organization are fundamental. Every tank, every container, every machine, every gauge, every thermometer, every pipette, cup, the floor: everything needs to be cleaned, cleaned again, and then cleaned again. In the case of Seis Mãos, the time that separates the end of the harvest from the delivery of the grapes by the partner producer is filled with conferences, organization and more cleaning. Masts sanitized, de-stemming machine shining, yeasts organized, instruments in their places.

Once the grapes are received, they are immediately weighed and go through the de-stemming process – the berries are separated from the stem, the stem – in a process affectionately known as ‘beating the box’. Think of the sound of boxes full of grapes hitting metal equipment. In the case of Pinot, multiply this noise by 57 times: it hits the box. At the same time, the must begins to fill the wooden mast, where it will remain for as long as the winemaker deems most appropriate.

The process described above seems simple, but remember: in the case of Pinot, there were 57 boxes or 850 kilos of fruit. On this day we started with Chardonnay, harvested from another vineyard in the same region: 500 kilos of fruit, I didn’t even have time to count the number of boxes, but do a mental exercise.

Hours later, mastelas filled, it was time to make Pé de Cuba – in other words, dilute a preparation to add yeast to the must and wait for fermentation. It’s something very interesting and serious: by doing things in practice we realize more clearly the importance of knowledge and technique in making wines. And we value even more those who have the security and confidence to carry out these fundamental and delicate processes.

About the winery

For those who don’t know Seis Mãos, here’s a tip. A project that began informally back in 2014, when Carol Gonzatti made her first Chardonnay sparkling wine at home. In 2022, the winery was legalized and registered with MAPA. Why the brand? Six Hands, for Carol, represent the wine cycle: the farmer, the winemaker and the cooper, for her fundamental figures in the development of the product.

What about the wine that we start making at the end of January 2024? Now we have to wait for the time of the wine and the winemaker.

Pinto Bandeira

We left Monte Belo do Sul and drove fifty or so kilometers to the last stop, in Pinto Bandeira, a town known for the high quality of its sparkling wines. A quality that is so recognized that since November 2022, labels produced by four wineries in the region – Valmarino, Aurora, Geisse and Don Giovanni – can bear the Altos de Pinto Bandeira Denomination of Origin seal on their labels, the only D.O. of New World Sparkling Wines.

Altos da Pinta Vineyards

Our destination was Vinhedos Altos da Pinta, a property not very easy to find – but how good it is, we would say, a beautiful and peaceful refuge, where the couple Pedro Maciel and Renata Salvadori Rizzotto live, he is a journalist and she is an architect, in the middle of the nature and the ranks of Chardonnay.

At the front, in the area that already produces, there are 1,700 seedlings, planted in 2017. At the back of the land, a larger space has another 3,700 seedlings of the same variety, planted in 2020, all coming from Friuli, Italy. In the coming years, the idea is to also plant Pinot Noir, a classic grape used in the region’s elegant and award-winning sparkling wines.

Life project

But why make wine? “Wine became a life project”, says Pedro. When retiring, the couple thought about two options: living on the beach and doing nothing or moving to Serra and making wine. The duo, who have always shared healthy eating habits, opted for wine. “I think we’re crazy”, jokes Renata. “Even more so with this biodynamic option”, he adds.

The vineyard, certified by Demeter, follows the philosophy of Rudolf Steiner, uses preparations, follows the phases of the moon and has practically zero intervention. The harvest is done on the rising moon, full moon, which means, says Renata, that there is a lot of sap in the plant, leaves and fruits. “Our next harvest will be on a fruit day, ascendant, full moon and Leo, everything favors”, explains Renata. “We make the wine we think is right. And each wine is right for each person: there is room for everyone”, explains Pedro.

“If biodynamics still has a disadvantage, it is because it is little known, which makes it more expensive, which complicates the sale of the product”, he says. According to Pedro, the biodynamic wine drinker either knows the product or is curious about trying new things – “and when they try it, they usually like it”, he adds.

The two labels of Chardonnay dos Altos da Pinta – a sparkling and a still – are produced from autochthonous or indigenous yeasts – those that occur naturally in each region and in this way guarantee typicality to the drink – they do not undergo filtering, chaptalization, they do not have additives or clarifiers and receive less than the authorized minimum of sulfite. “We make wine from grapes”, says Pedro.

All this care – and why not say restrictions – takes its toll: in 2023, for example, Altos da Pinta produced only 139 bottles, think of artisanal production. The expectation, according to Renata, was around 2 thousand units: “but then there was frost, rain and birds”.

You can’t go against the weather, but the birds have one more obstacle: the entire vineyard is protected against them.

For material suggestions, write to [email protected]

text and photos: Lucia Porto